Kütahya, which was the second largest tile production center after Iznik during the Ottoman period, was a city where ceramic production was intensively carried out during the Phrygian, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods due to the rich clay deposits in its surroundings, and where this art is still traditionally kept alive today.

While studies on the state of ceramics production in Kütahya, a city that holds a significant place in Turkish tile history and has experienced a long and continuous ceramic production, are still scant, recent finds and publications indicate that it shares a certain parallel with İznik and suggests similar production. Faruk Şahin, who studied ceramic pieces recovered during a 1979 infrastructure excavation in Kütahya, stated that Kütahya was contemporary with İznik in terms of ceramic production. Among these finds are examples of ceramics that began in the early Ottoman and Beylik periods, and are universally accepted as having originated in İznik, although this is misnamed as "Miletus ware." These red-pasted, white-slipped ceramics, some featuring incised (sgraffito) patterns, are adorned with abstract flowers and simple geometric motifs in deep cobalt blue, manganese purple, turquoise, and black. Faruk Şahin stated that these ceramics, reflecting slight differences from İznik production, are considered domestic production. While they share the same characteristics as those produced in Iznik, these examples have a thinner glaze and small cracks. Furthermore, the darker tones suggest these pieces are closer to the colors of Anatolian Seljuk tiles.

The earliest tiles in Kütahya are the monochromatic glazed bricks on the minaret balcony of the Kurşunlu (Kasımpaşa) Mosque, dating back to 1377. Other early examples include the turquoise-glazed hexagonal and triangular panels used in the sarcophagus and floor covering of the 1428 mausoleum of the Germiyanoğlu II. Yakup Bey Soup Kitchen, now the Kütahya Tile Museum, and the colored-glaze border tiles with rumi and palmette patterns. Furthermore, the turquoise-glazed panels covering the walls and floor of the narthex of the İshak Fakih Mosque, which had been converted into a mausoleum before restoration. The decoration of these tiles is similar to the tiles of the Muradiye and Yeşil Medreses in Bursa, and this similarity is considered an indicator of the ties between Kütahya and Bursa.

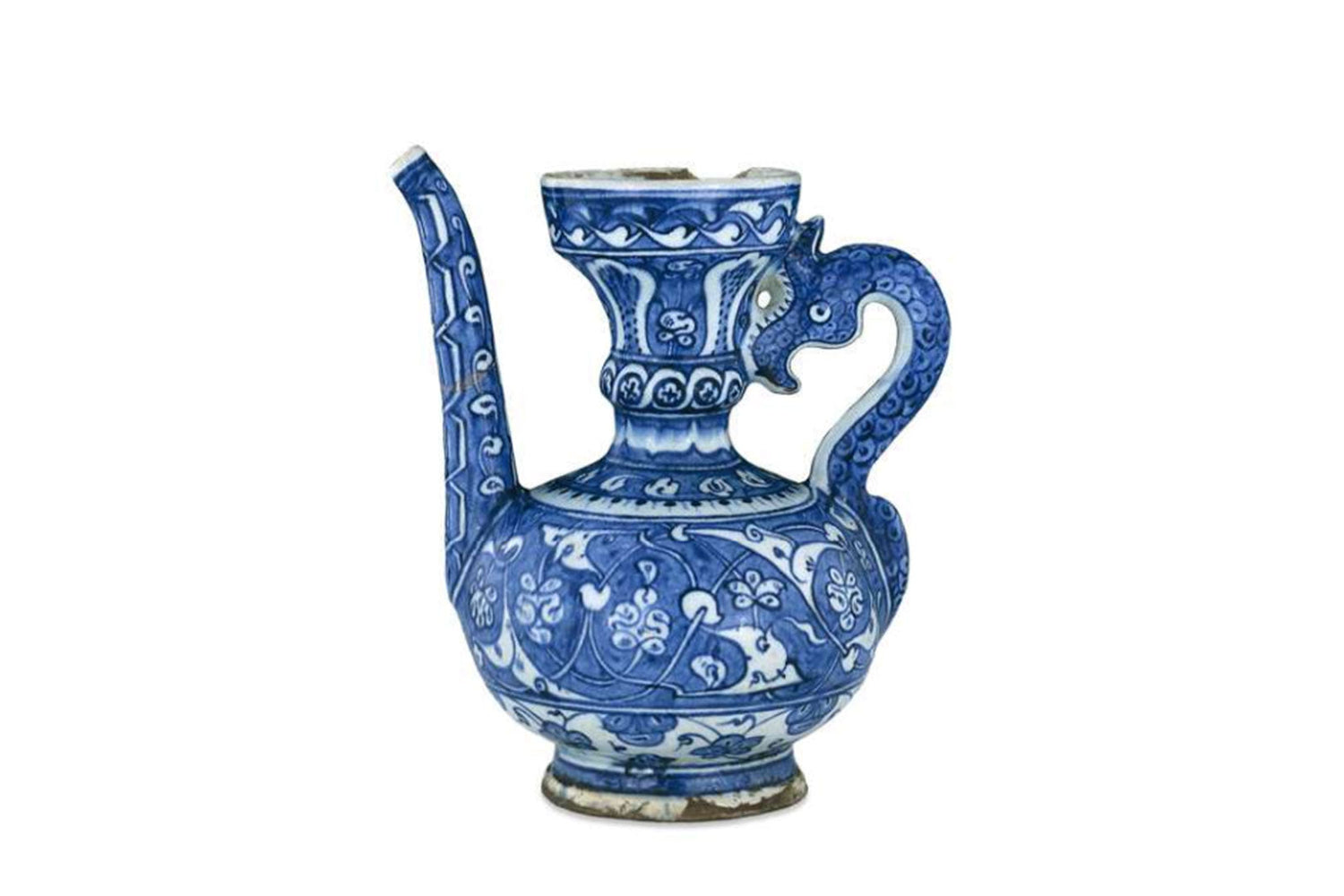

Two of the most famous examples of 16th-century Kütahya ceramics are currently housed in the British Museum in London (Godman Collection). The first of these is a jug with an Armenian inscription, dated 1510. Notable for its distinctive form, this jug bears a six-line inscription on its base: "In memory of Abraham of Kütahya, servant of God, on the 11th of March of this year 959 (1510)." Adorned with Rumi and Hatayi motifs, the jug's dragon-shaped handle is decorated with fish scales. This decoration will reappear in a more stylized form in 18th-century Kütahya ceramics. The other is a pitcher with a broken neck, commissioned from Kütahya in 1529 by Bishop Der Mardiros as a gift to a monastery in Ankara. The Armenian dedication inscription at the base prominently reads "Kütahya work." This jug, which is further evidence that Kütahya masters produced in parallel with İznik, shows that İznik was not the only production center of the ceramics called "Golden Horn work" or "spiral tugrakesh style" and that Kütahya masters had a market extending as far as Ankara.

While there is some information on Kütahya's blue-and-white patterned ceramics, dating to the late 15th and early 16th centuries, there is no information on mid-16th and 17th-century ceramics. Therefore, Ottoman tiles and ceramics produced in the 16th and 17th centuries are generally considered to be made in İznik.

Documents destroyed in the fires of the Evkaf Office and the Sharia court records have obscured many aspects of Kütahya tilemaking. According to those who saw these documents before the fire, Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha established a tile workshop next to the madrasah he had built in the Balıklı neighborhood of Kütahya and commissioned tiles for the mosque named after him in Eminönü, Istanbul. Because some of the panels in this mosque differ in style from İznik tiles, it has been suggested that they may have been made in Kütahya. Another theory is that Mimar Sinan sent the designs he had drawn by muralists to various workshops in both İznik and Kütahya, and that, preferring examples from İznik, he commissioned the tiles for the Süleymaniye Mosque to be made by İznik masters. This demonstrates that İznik, which received the support of the Palace, was more prominent than Kütahya, and also points to the existence of a developed tile production in Kütahya. However, it is also important to keep in mind that coral red tiles, the characteristic color of this century, are not found among the Kütahya finds.

Written documents clearly demonstrate the prominence of Kütahya tilemaking in the 17th century. A decree dated 1607-8 to the Kütahya judge indicates a dispute between İznik and Kütahya over raw materials. A price record book from 1600 indicates that, as the quality of İznik ceramics declined, Kütahya ceramics entered the Istanbul market and began to be sold at a higher price than İznik products. The estate of Hacı Hürrem Bey, dated 1623, records 12 İznik ceramics, 7 chinaware, and 1 Kütahya plate. It is noteworthy that the İznik plate was valued at 60 akçe, the Chinese porcelain at 150, and the Kütahya plate at 500 akçe.

In his Travelogue, the renowned traveler Evliya Çelebi noted that İznik and Kütahya plates were displayed together in a parade held in the presence of Murad IV in 1633. He also noted that when he visited Kütahya in 1671-72, there were 34 workshops in the infidel tile neighborhood of Kütahya, while İznik had only nine tile workshops. He also noted the beauty of Kütahya tiles. This demonstrates that while production in İznik had declined, Kütahya tiles maintained their vibrancy.

At the beginning of the 18th century, tile production in Iznik virtually ground to a halt. While Kütahya saw a surge in production, apart from a 1710 order of 9,500 tiles for the restoration of the palace of Fatma Sultan, daughter of Sultan Ahmed III, no other documents have been found in historical sources or archival documents indicating any other orders were placed with either Iznik or Kütahya. Çelebizade İsmail Asım's work states that tile orders were not placed with manufacturing centers like Iznik and Kütahya. This was due to factors such as the political concerns of state leaders and the fatigue of campaigns and war, leading to a decline in the value of tiles, thus impoverishing those involved in this art.

In Kütahya, in the 18th century, everyday vessels and religious objects were also produced in forms designed to meet the daily needs of the people and never used in İznik. Far Eastern influences are very evident in the pottery. But most notably, a vibrant yellow color, never seen in İznik ceramics, was used in Kütahya tiles and ceramics from the beginning of the century onward.

From the second half of the 18th century onwards, it is observed that the quality of the dough and glaze deteriorated, the paints flowed and the drawing in the patterns weakened.

After the 19th century, there was a revival in tile and ceramic production. With the Second Constitutional Era, the field of architecture was also affected by political, social, economic, and cultural changes, and a new architectural movement emerged, particularly based on the ideas of Ziya Gökalp. The fundamental characteristic of this movement, known as the First National Architecture Movement, was its adoption of structural elements from Seljuk and Ottoman architecture and the prominence of tiles in the decoration of buildings, as required by the architectural style. In line with this movement, official and private buildings in major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, and Konya were decorated with Kütahya tiles. The quality of the paste and glaze improved considerably, and the patterns were modeled after 16th-century İznik tiles.

In the early years of the Republic, the number of tile and ceramic workshops in Kütahya increased with government support. Today, Kütahya boasts many workshops, and mass production is still carried out for tourist purposes rather than traditional production that perpetuates the past ("Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics," pp. 9-15).

If you would like to see the Kütahya tile ewer exhibited in the British Museum in London, you can click on the link below.