Tiles, one of our traditional art forms, have been among the most elegant ornaments used in architectural structures since ancient times. The tile adventure began with the Karakhanids' conversion to Islam and accelerated with the Anatolian Seljuks. Tile art reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the underglaze technique was frequently used.

Tiles, which frequently adorned mosques and palaces during the Ottoman Empire, are also found in the Prophet's Mosque in Medina. The Prophet's Mosque, initially quite plain, retained its modest structure for the first 80 years. Its introduction to ornamentation and mosaics occurred during the Umayyad period. During the reign of Walid ibn Al-Dulmalik, the Prophet's Mosque was both expanded and its decoration was given special attention. Caliph Walid contacted the Byzantine Emperor for this project and requested specialized craftsmen from him. Forty large mosaic panels and 100 craftsmen were sent from Damascus to the Prophet's Mosque to handle this task.

After two major fires in 1256 and 1481, the Masjid al-Nabawi underwent extensive renovations. The gold mosaics and priceless motifs from the past remained on the walls. The Masjid al-Nabawi's introduction of tiles, one of the finest examples of Ottoman aesthetics, occurred during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.

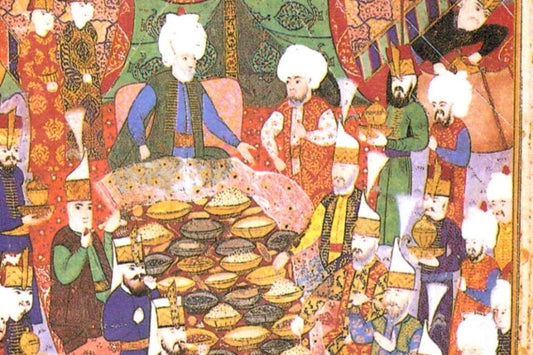

Sultan Suleiman requested reports regarding the Prophet's Mosque. These reports led to the decision to install tile panels in addition to the Mamluk marble. Between 1532 and 1540, the exterior walls of the Hujra al-Saadat were decorated with bright Damascus tiles. Approximately 250 of these tiles are known as the first tiles in the Prophet's Mosque.

Ottoman sultans paid particular attention to the maintenance, repair, and beautification of their holy sites. An archival document mentions a construction project at the Masjid al-Nabawi during the reign of Sultan Mehmed III, in which 124,649 gold coins were spent. The production and installation of the second type of tiles for the Masjid al-Nabawi also coincided with this period.

The density of tiles in the Masjid al-Nabawi increased during the reign of Sultan Ahmed I, and these specially produced tiles added a distinct aesthetic touch to the sacred space. The finest examples of 16th- and 17th-century tiles, considered the pinnacle of Ottoman tile art, appear in Medina during this period. These tile panels are identical to those produced for the Sultanahmet Mosque. It is likely that the same panels were also sent to the Masjid al-Nabawi when tiles were being produced in Iznik. It is a well-known fact that Sultan Ahmed Khan was filled with love for Muhammad. While he was commissioning a magnificent mosque in Istanbul, he did not neglect the Masjid al-Nabawi, sending the finest of its precious tiles there.

On November 4, 1907, Istanbul was informed that the tiles in some areas of the Hujra al-Saadet (Celestial Chamber of Sacred Hearts) and the Prophet's Mosque needed to be renewed. A diagram of the existing tiles was drawn, and the palace was presented with the exact quantity needed for each location. According to archive documents, 5,040 tiles were manufactured in Kütahya within a short time. These were the last tiles produced by the Ottomans for the Prophet's Mosque ('Treasures of the Earth, Fatih Karaboğa, pp. 373-384).