While glazed decoration, mainly tile mosaics, was applied together with underglaze tile panels that we find in palaces during the Anatolian Seljuk period, a small amount of tile mosaic decoration is found in the 12th century Anatolian Turkmen Principalities.

The Orhan Soup Kitchen in İznik is perhaps the first structure in Ottoman architecture to utilize tile decoration. The lower portion of the soup kitchen's walls is clad in green and turquoise hexagonal panels. The minaret of the Yeşil Mosque, also built in İznik in 1378, stands as an example of the Seljuk tradition, further enriched by the use of mosaic tiles and glazed bricks. The mosaic tile tradition continued on the Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen, the mosque facade of the Bursa Murad II Complex, and various sections of the mosque and mausoleum within the Yeşil Complex, sometimes within the brickwork, occasionally between the stones, and even disappearing into the white plaster surfaces on the floor. The final applications of this technique in Istanbul during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror are seen in the exterior iwan of the Tiled Kiosk and the Mahmut Pasha Tomb.

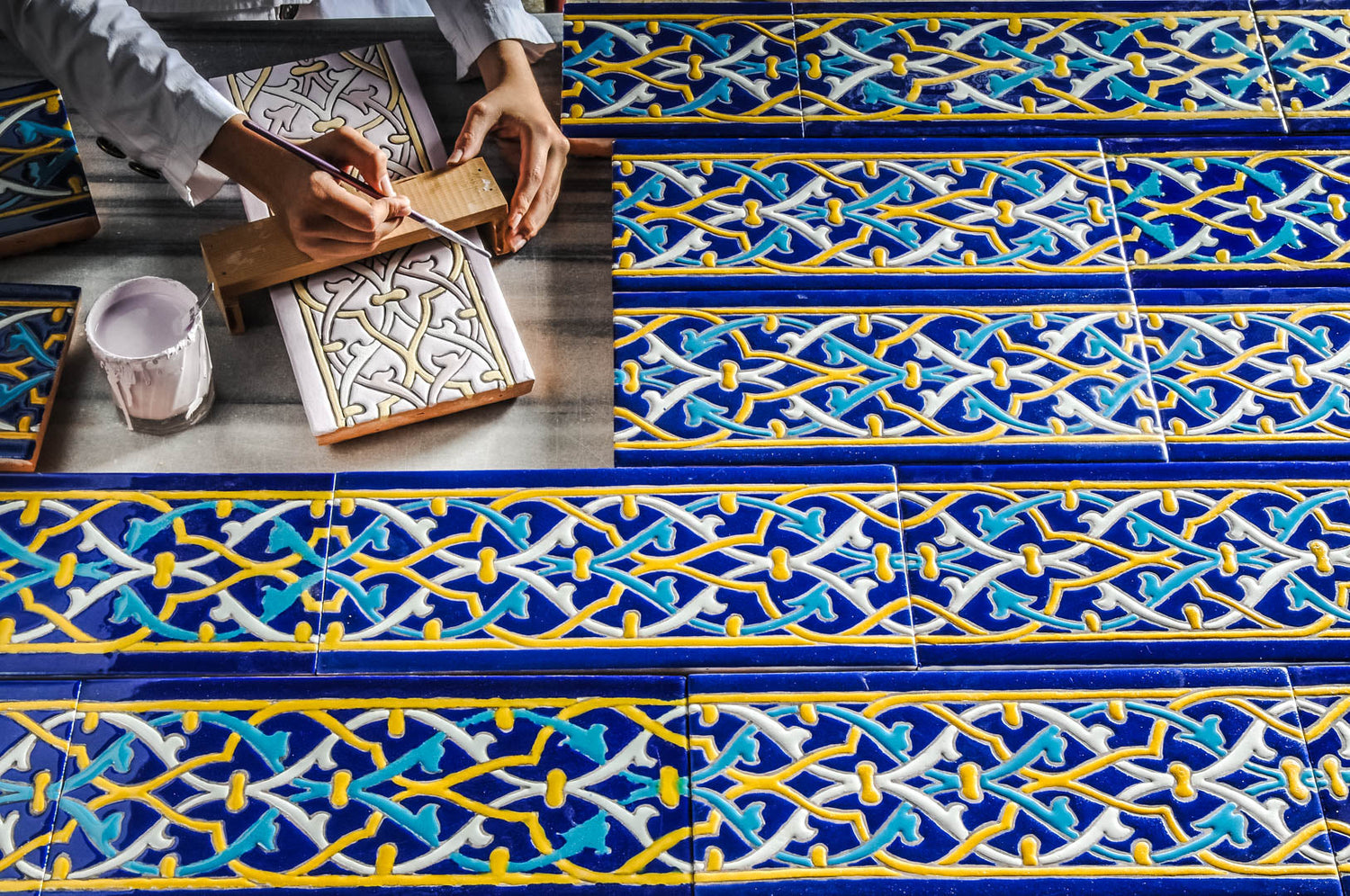

The most striking development in early Ottoman architectural decoration can be seen in the colored glaze technique, the most mature examples of which can be seen in the Green Tomb and Mosque in Bursa. The decorative program in this complex, where masters from Tabriz are also known to have worked, was led by Ali bin İlyas Ali of Bursa, known as Nakkaş Ali. This artist, taken to Samarkand by Timur, must have returned later. In the Green Complex, between 1421 and 1424, a diverse tile decoration program was successfully applied to the walls, mihrabs, gallery and iwan ceilings, and sarcophagus, with vegetal curves and raised and circular surfaces. The matte red applied after firing on the colored glaze tiles, which distinguishes colors with contours, is striking as a type of hardened paste. This color, understood to be crystallized mercury sulfide, was the precursor to the raised red underglaze color in later İznik tiles and ceramics.

The Green Complex, where various techniques were employed in addition to the application of gilding over glaze on flat tile panels, serves as a laboratory for Ottoman-era Turkish tile art. The tiles in the Green Tomb are not only remarkable for their exceptional decorative quality but also for the composition of the underlying clay. A special mixture was used to achieve excellent results on various surfaces. The tiles, made of red clay obtained with a high content of free quartz and silica, were produced according to specific needs, with a certain level of knowledge and experience. It is likely that they were designed on-site according to the decorative program and fired in local kilns. It currently seems impossible to evaluate the very small tile fragments from the Iznik excavations, which indicate the use of colored glazes, on a scale that would refute this idea.

Production in the colored glaze technique, after various examples such as the mihrab of the Muradiye Mosque in Edirne, the Tomb and Mosque of Yavuz Sultan Selim in Istanbul dated 1522, and the mihrab of the Karaman İbrahim Bey Soup Kitchen dated 1432, which is currently on display in the Tiled Kiosk, perhaps produced its last magnificent examples in the Tomb of Şehzade Mehmed in Istanbul dated 1548 in the 16th century, and gave way to the underglaze technique.

The first examples of underglaze tiles from the early Ottoman period are found in the Muradiye tombs in Bursa. Their blue-and-white decoration is striking. Perhaps the most striking blue-and-white underglaze wall tiles of the 15th century are found in the Muradiye Mosque in Edirne. These hexagonal tiles, of which thirty-seven different examples have been identified, cover the lower part of the walls and are connected by triangular flat panels.

It appears that İznik began to come to the forefront in the production of wall tiles, in addition to ceramics, from the first half of the 15th century onwards. The Seljuk connection in red-paste scratching and slip painting techniques in ceramics began to transform into early Ottoman ceramics with white slips and free-flowing blue decorations. From the second half of the 15th century onwards, changes in clay and decoration occurred, and from the first half of the 16th century onwards, a naturalist style developed. While İznik played a decisive role in this period, recent research has demonstrated that Kütahya also underwent a similar stylistic development using a different clay ('Treasure of Anatolian Soil Tiles', Belgin Demirsar Arlı-Ara Altun, pp. 19-21).